Ever since researching the history of Cardiff High School for Girls I’ve been keen to find an example of an ex-pupil from the early days of the school who became a successful scientist and I’ve just found her. Mary Pugh was a very successful eye surgeon, specialized in correcting eye squint and developed the Pugh orthoptoscope.

She was born Muriel Agnes Pugh but later changed her name to Mary Pugh as she disliked the name Muriel. She was born in Barry on 11 May 1900. Her father was a commercial traveler in the drapery business and originally came from Aberdare. Her mother, Agnes Mary Pugh née Jones was from Bath. When Muriel was young the Pugh family relocated from Barry and settled in Roath, living at 67 Bangor Street. Muriel attended Marlborough Road School before moving onto Cardiff High School for Girls in 1911. They later moved to 9 Marlborough Road where they were at the time of the 1921 census.

The head teacher at Cardiff High School for Girls at the time was Mary Collin, an active suffragette. She taught her pupils to ride bicycles, seen as a symbol of the growing independence of women and their determination to cast off chaperonage. The amount of science taught at the school was probably fairly limited when it started up in 1895 but by the time Muriel joined in 1911 things were probably beginning to change.

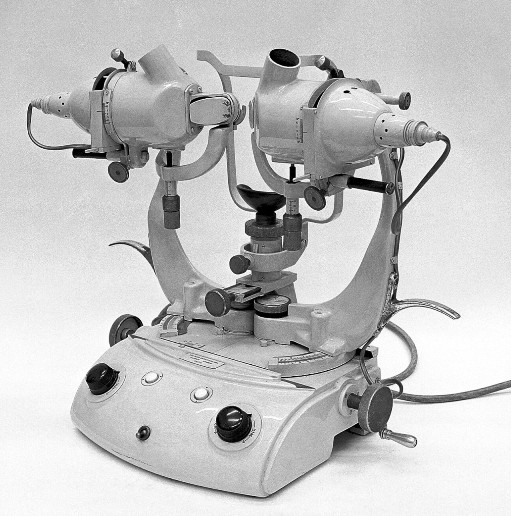

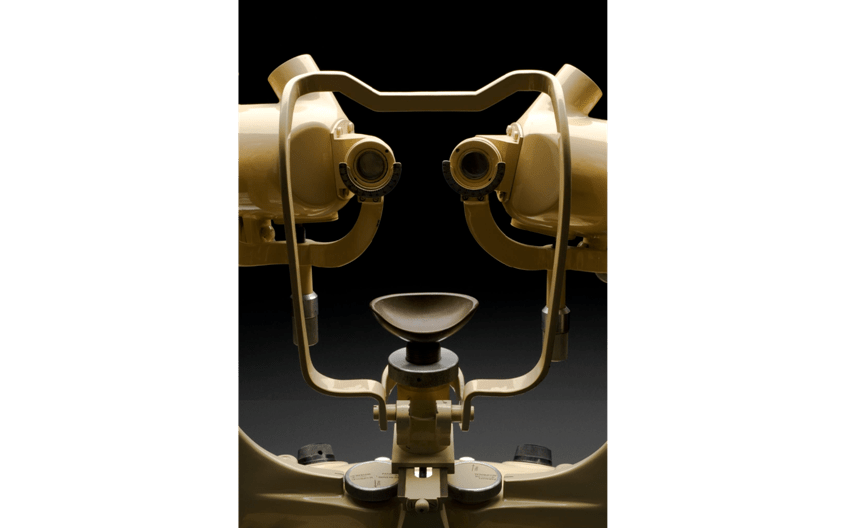

She left school in 1918 and went on to read medicine at Cardiff Medical School. She then did her clinical training at Charing Cross Hospital and qualified in 1926. She was initially employed at Birmingham and Midland Eye Hospital before moving back to London and working at Moorfields Eye Hospital in 1928 in the Squint Department where she was made Officer in Charge a short time later. Her work in that department led her to developing the Pugh Orthoptoscope, an instrument to investigate and correct eye squint. Her work has been described as individual and pioneering and led to the development of modern day instruments.

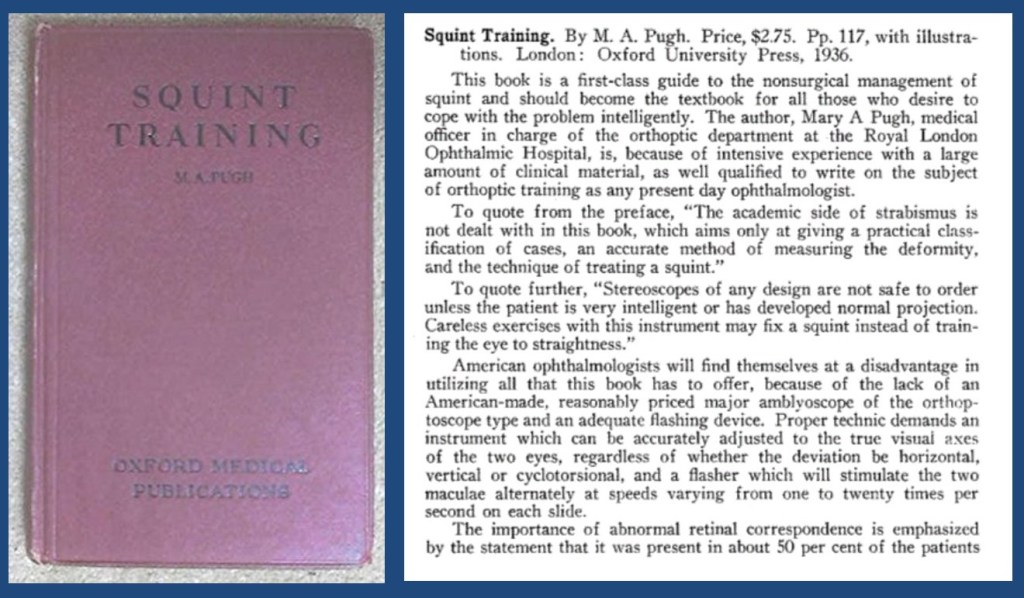

She stayed as leader of the squint department at the famous Moorfields Eye Hospital until 1948 during which time she authored the book Squint Training in 1936.

In 1948 she moved to the Institute of Ophthalmology where she worked on a part time research basis until she retired as well as working privately.

As well as a love of the arts she also enjoyed her cars and owned a Rolls Royce.

So why can’t I show you a picture of Mary Pugh? Perhaps it is because of her shy nature revealed in her obituary on the British Medical Journal “Mary Pugh was a bright, friendly person, shy and self-effacing, and intensely interested in the arts, especially painting and literature. She travelled widely and had an international circle of friends both medical and lay; indeed her ability to detach herself completely from her profession was remarkable. She will rank as a pioneer in her field and will be remembered with warm affection by all who knew her and with gratitude by a host of patients”.

I’ve also been informed that Mary Agnes Pugh became eye surgeon to both the Queen Mother and Queen Elizabeth.

She died in London on 21 Jan 1972 aged 71. She left her estate to Audrey Russell.

It would be lovely to hear from anyone who does have a picture that could share of Mary Agnes Pugh.

Her partner in life was Audrey Russell, the first lady of broadcasting, whom she met in war-torn London. They shared a love of theatre and the arts.

Audrey Russell was a pioneer of broadcasting. She was born in Dublin and educated in England and France. She trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama before becoming an actress and stage manager. Audrey Russell joined the BBC in 1942 after being discovered by them when interviewed about her wartime work for the National Fire Service. She travelled to mainland Europe just after the D-Day landings and reported from Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, and Norway.

In 1953, Russell gave a live commentary on the Coronation of Elizabeth II, from inside Westminster Abbey. She also gave commentary on the funeral of Winston Churchill in 1965. Martha Kearney on the BBC War Correspondent Audrey Russell.

Article compiled with the greatful assistance and input of Ingrid Dodd née Pugh.